Why No One Can “Come Together” — When Ringo Says He Couldn’t, But the Record Says Someone Did

A closer look at the most famous drum fill in the Beatles’ catalog — and why it might not be Ringo playing it.

Before we get to the Beatles’ most famous drum fill, it’s worth remembering how records were actually made in the ’60s and ’70s — and why what you hear on a record might not be who you think you’re hearing.

1. How the Pros Made the Records You Love

In the 1960s and ’70s, most people imagined their favorite bands walked into the studio, played exactly what ended up on the record, and walked out.

The truth? There was often a quiet “fifth member” in the room — the session player.

Hal Blaine and the Wrecking Crew are the textbook example. When I was learning to play drums and really listening closely, I played along with the Beach Boys’ “I Get Around” because it has a very simple beat and a straightforward snare fill. But it wasn’t just simple — it was tight. Laser-tight. I remember thinking, There’s no way a teenage kid like Dennis Wilson played that cleanly. I vaguely recalled Hal Blaine might’ve been involved — so I looked it up. Sure enough, Blaine played it.

Session drummers like Blaine often had to keep things simple — because the onstage “talent” had to mimic the parts live. But the studio version had to be pistol-hot — punchy, clean, and built for radio.

It wasn’t that Dennis Wilson was a bad drummer. It’s that Hal Blaine could deliver exactly what producers needed in one or two takes — which kept costs down and quality up.

This pattern wasn’t limited to drums. The same applied to guitar, bass, keyboards — even lead vocals. If a part wasn’t strong enough, it could be doubled, replaced, or “fixed” — often without the band’s fans ever knowing.

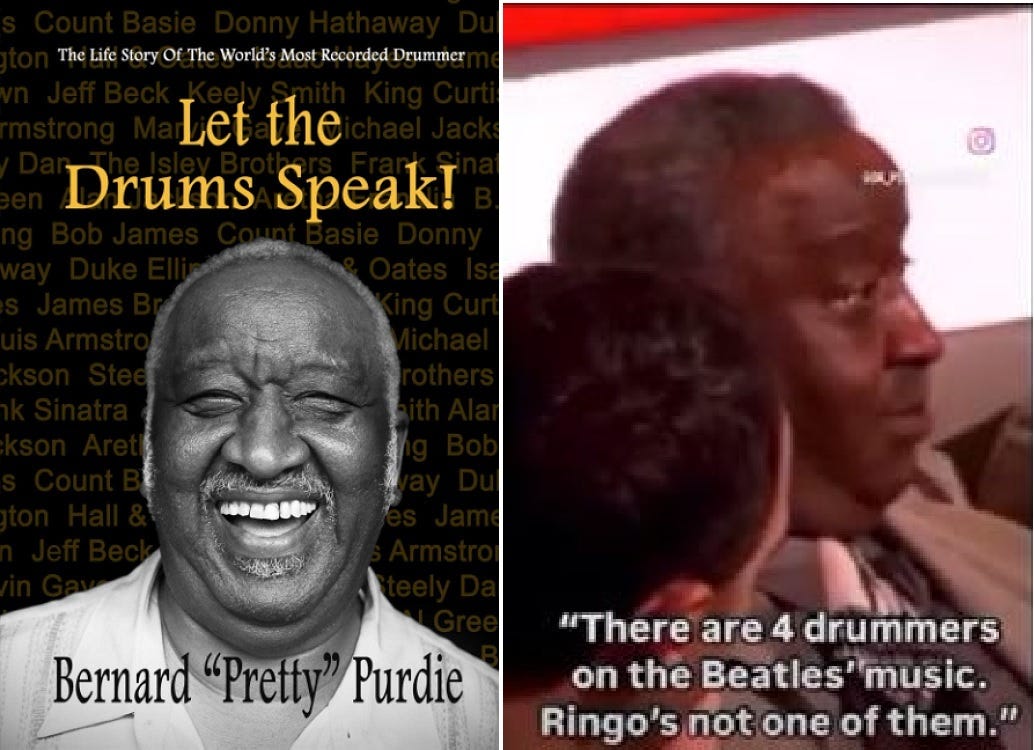

Bernard Purdie, one of the most recorded drummers in history, has spoken openly about this. He once claimed he was hired to “fix” 21 Beatles tracks — sometimes adding drums to songs that had none at all. He is quoted as saying:

“I’ve fixed a lot of records. That’s what they paid us to do — come in and make it sound right. Sometimes they’d tell you whose record it was, sometimes they wouldn’t. Didn’t matter. You did the job.”

At a 2004 Red Bull Music Academy event, Purdie stated that in the ’60s and ’70s, “ninety-eight percent of the groups — self-contained groups — are not on their own albums.”

Once you understand how common this was — even for the biggest bands in the world — it changes how you hear a lot of so-called signature performances.

2. Ringo’s Claim — “I Can’t Play Descending Fills”

Now we come to Come Together — the lead-off track on Abbey Road, the Beatles’ final and arguably most polished studio album. It features one of the most recognizable and unusual drum fills in rock history.

It’s been debated for years how Ringo, a left-handed drummer playing on a right-handed kit, accomplished that descending tom-tom fill — a smooth roll that moves from the high tom to the floor tom.

Ringo has said in multiple interviews that because of his setup, he can’t play descending fills the way a right-handed drummer would. Instead, he says he starts from the floor tom and plays upward — effectively backward from what most drummers do.

One of the clearest demonstrations of this comes from an interview with Dave Stewart of Eurythmics fame. Ringo sits behind the kit, explains his limitation, and plays the Come Together fill “the way he did it on the record” — except in his demonstration, the fill clearly ascends, not descends.

3. Vintage Drummer’s Perspective

This is where my curiosity deepened — thanks to the YouTube channel Vintage Drummer.

In his original Come Together drum cover, he nails the intro fill exactly as it sounds on the record — starting high and rolling down. As a beginner myself, watching someone pull off those descending fills cleanly was impressive. It takes coordination and finesse — not something you fake or fudge.

What stunned me was his commentary. Not only did he acknowledge that the recorded fill is absolutely descending, he stated outright that Ringo must be misremembering — because what’s on the record contradicts Ringo’s own explanation.

4. Gary Astridge’s Anecdote

After the cover gained traction, Vintage Drummer released a follow-up video addressing the controversy. In it, he shared a story from Gary Astridge, Ringo’s official drum curator.

This is a most interesting wrinkle coming from Gary. In the interview referenced by Vintage Drummer, Astridge recalled watching Ringo sit down at his first Ludwig “Downbeat” kit before it went to auction. According to Astridge, Ringo launched into the Come Together groove starting from the high rack tom down to the floor tom — the very descending motion Ringo has said for decades he “can’t” do on a right-handed kit. Astridge says Ringo caught his eye, laughed, and made a comment as if to say, “You noticed that, didn’t you?”

Vintage Drummer took this as proof that Ringo was more capable than he remembered — that perhaps it was just a matter of faulty memory.

For me, the laugh is telling. It doesn’t prove what’s on the record — and it could just as easily have been Ringo goofing around, experimenting with a different feel, or even parodying the way fans think he played it. What it does prove is that Ringo is aware there’s a story here, and that his public explanation doesn’t quite cover all the angles.

And that gap — between what’s been said and what’s been heard — is where the real questions live.

5. My Take — and the Precedent for “Fixing”

Here’s what still nags at me: Why does almost no one even consider that someone else might’ve played that fill? Or that it was fixed after the fact?

This isn’t just speculation. There’s a documented precedent inside the Beatles’ own recording history. On Can’t Buy Me Love, a tape defect ruined the high frequencies of Ringo’s hi-hat in the master. With the band unavailable, producer George Martin brought in engineer Norman Smith — a skilled drummer — to overdub the missing hi-hat. That “repair” made the final stereo mix.

If a hi-hat was worth fixing by a stand-in, imagine the incentive to nail the opening fill of Come Together — especially a fill that Ringo has repeatedly said he couldn’t play?

After all, it is the lead track on Abbey Road and the band’s final statement as a group. Whether that meant a quick substitution, a drop-in fix, or a full second take by someone else, it would have been completely in line with industry practice at the time.

6. And in the end…

In the end, Come Together leaves us with a simple question:

When the sound on the record doesn’t match the story we’ve been told — do we accept the story, or do we follow the evidence?

It's highly unlikely that Ringo is on the track. My guess is either Alan White or Jim Keltner.